Wedding Magic (2)

NEX-6, 50mm E-Mount Lens @ 50mm, Aperture Priority Mode, 1/800 secs, ISO 100, f/1.8

Despite my first ‘Wedding Magic’ photo being only 4 posts ago, I couldn’t resist using this image of my friends, Dion and Caroline, which I took at their wedding this weekend. With no more weddings on the horizon, and the fact that I love the happy couple’s expressions, stances and movement, I thought that I might as well tick off the second wedding photo from the list. This post will only feature two photographs, however, as I aim to discuss the magic that can be added to photos with the help of processing software such as Aperture 3 or Lightroom. I use Aperture 3, but Lightroom isn’t too different (from what I have read) and you can essentially create similar effects with either tool. Here is the original photograph, that I took in RAW format, straight from the camera without any improvements:

The Bride & Groom arrive at the reception, where a tunnel of guests with confetti await. I was not the official photographer, and so I didn’t want to start jumping in and snapping away as though I were. I had spent the majority of the event taking photos of friends, leaving the Bride & Groom in the safe hands of the professionals, but I couldn’t resist getting in on the action as they arrived, albeit from a less favourable position than the official photographer.

Anyway, now on to my workflow process…

Once I have loaded all of my photos in to Aperture 3, I take a quick run through selecting the best (I simply ‘flag’ them, but pros probably use star ratings) and deleting the worst. I will probably go through the shots a few times before settling on my overall favourites, which lets me get to know each of the shots fairly well. Then the editing process can begin, with my first port of call almost always being the ‘Auto Enhance’ (Magic Wand) Button, which you can find just under the histogram, on the Adjustments tab, next to the Add Adjustment and Effects drop down lists. That tends to do something like this:

You can see that the image is now punchier and more vibrant, as the software has made certain decisions on how the image can be improved, by changing things like the White Balance, Saturation, Vibrancy, and it also makes some small adjustments with the Curves tool. My photo is generally OK I guess, but it lacks that certain something that great wedding photos have, and is slightly spoiled by the official photographer being in the way of the Groom. To me, wedding photography is all about the expressions on faces, with the addition of some drama and feeling which is created by the photographer playing with things like the colour in their post-processing software, even if that means removing the colour and creating a black and white image. Therefore, what this image really needs is a good crop, so that we can see the expressions of our subjects clearly, and remove any unwanted elements from the scene. After hitting ‘Auto Enhance’, I generally then move on to cropping and straightening my images before getting too involved in making further adjustments – I think it helps to know what you’re going to be working with before you start adjusting areas of a photo that you are later going to crop out. This is how my first final image turned out:

B&W final image, cropped to remove the official photographer and to really show the joy on the faces of the Bride & Groom.

I don’t want this to read as a tutorial on how to use Aperture 3 – it is intended more to introduce you to some of the features that can seem rather daunting and confusing when first using the software. For instance, it is easy to convert an image to B&W by moving the Saturation slider to the far left, which simply removes all colour from your image. However, you will get much better results by adding the ‘Black & White’ adjustment, and playing with the Red, Green and Blue sliders, which give you total control over every shade of Black, Grey and White in your image, letting you choose which areas are darker and lighter.You can then Dodge, Burn, change Exposure and Contrast (amongst other things) to really make your final image shine.

I am by no means a professional at playing about with images, and it has taken me quite some time to get to grips with what each slider and Adjustment does to an image, but I have grown gradually more and more confident through general use of Aperture 3, and watching tutorials on YouTube and putting what I learn from those into practice. As I was never a child genius or anything like that, I have had to learn bit by bit, rather than watching all of the tutorials available and suddenly knowing and understanding exactly everything about the software. However, I have had several epiphanies about how things work and fit together along the way, with my latest coming after another round of watching a load of tutorials in the last week or so, and this latest has kind of made feel as though I am really beginning to understand the software and its possibilities. Here is a list of my main ‘Eureka Moments’ with Aperture 3, which may help you and give you ideas of what to look for on YouTube as well, starting from the beginning, when I first realised what a RAW file was:

- Shoot in RAW – I cannot stress this enough! If you do not believe me, set your camera to shoot both RAW and JPEG, and shoot one image with good contrast – say a sunny landscape with plenty of sky, white clouds and darker greenery in the land. Put both versions in to your editing software of choice, and start playing around with the exposure slider – you will start to realise just how much information is lost when your camera converts an image to JPEG itself.

- Take time looking through the various Adjustment sliders and seeing what they do for your images – just stick with the basic options that are added as standard by Apple to the left of the screen when you first open an image (I’m not sure how Lightroom handles these), as these are basic options that will really improve your image in small but significant ways, affecting things like Exposure, Colour Saturation, Shadows, the Black Point and Contrast. With these, you will effectively be making the decisions that your camera automatically would when shooting in JPEG format.

- The Quick Brushes are great for making targeted adjustments to your images, whether that be dodging and burning or removing dust spots from the image and wrinkles from faces! Again, watch some online tutorials on how to use the dodge and burn tools (I’m still having some difficulties getting these to work well for me, but I need more practice with them).

- Start to learn about Curves and Levels – type ‘Aperture 3 Curves Tutorial’ into YouTube and be prepared to be amazed at the possibilities. Do the same with ‘Levels’, then start applying these to your own photographs, to really increase contrast and get some different effects.

- Learn to experiment with the individual colour channels in the Curves adjustment. These can give your photos a professional-looking tint, and really make it stand out (in conjunction with other alterations of course). I realise that it may not be everybody’s cup of tea, but I really liked the following photo of my friend, Alice, seeing that it had some potential in an arty kind of way. Using a combination of Curves adjustments to the RGB spectrum and then the Red spectrum alone, along with Levels adjustments and so on, I think that I made it realise its potential and bring out more of what I wanted to see in the original.

Straight from the camera – I enjoyed the blown out background and halo-effect it had on Alice, but the image looks washed-out with not enough contrast or vibrancy.

A few adjustments later, and the image is punchier, with a bit of a colour tint to compliment Alice’s eyes.

Back to the original photo now though, and whilst I was extremely happy with the B&W image that I had created, I wanted to try out a few different things with it, so my next idea was to change the crop to fit all of Dion and Caroline in the frame. This meant including a slice of the official photographer, unfortunately, and I also decided to give it a sepia tone – I’ve seen many wedding photographs done with a sepia tone, so it seemed to make sense to at least try it.

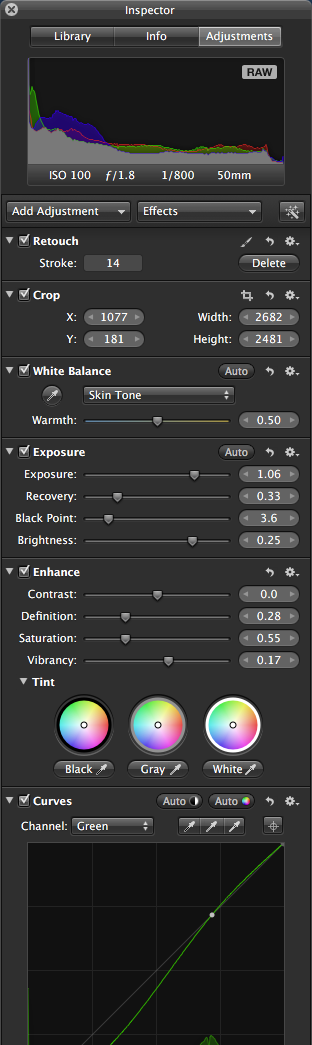

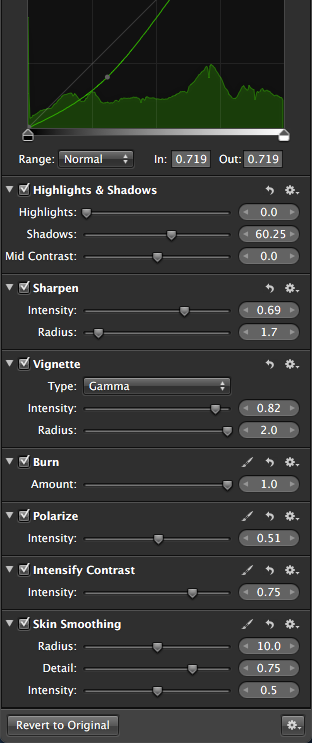

As a rank amateur, the only way to learn is to practice and try different methods until you start to get a better feel of what works for you. In the above image I was happy with the idea of seeing the Bride & Groom from head to toe, but the smile on Caroline’s face, and the fact that she appears to be looking straight into the camera, made me feel that she should be placed centrally in the next frame I was to attempt – which would turn out to be the featured image, and the one that is without doubt my favourite edit of any photograph that I have ever achieved. To give you an example of what sort of things that I did to get the final image, I have taken some screen shots of the Adjustments that I added to the photograph. There is no point in copying them, as every photograph is different, but it would be worth while seeing how each of them affects your own images. This is the standard set of adjustments that Aperture 3 gives you when opening a new image:

I needed to use two screenshots to get the full length of final adjustments that I used for the featured image:

They don’t quite match up in the middle of the Curves adjustment, but you should get the general idea. The areas that interest me the most right now, as this was the first time that I had really used them, are the change to the Green Curve, the reduction of the Saturation, and the use of the Polarize and Intensify Contrast Quick Brushes. It is often easy to boost Saturation, when in reality you can get a much more interesting result by decreasing it. At the end of the day, you need to take each photo on its own merits and try out a few different techniques to find the one that suits it.

Above all though, please remember that getting to grips with this type of software will probably take practice and patience, so take your time and learn the basics well before trying to do too much with your images. In my experience at least, it is too easy to read about techniques and think that they will suddenly be easy to replicate, when in reality it can take a bit of experience to really appreciate and refine your use of them.

Well, I hope that this post hasn’t been too boring, but during my own attempts to find ways of using Aperture 3 to make my photos look more professional I wasn’t able to find a great deal about how the Adjustments could be mixed to get different results. Therefore, I hope that this has been of some use to others in a similar position to myself, and if you have any gems of wisdom to share with me and others then please do so in the comments section. Another quick tip that I can give you though, is that using the full screen option for Aperture 3 is a real joy – just remember to hit the ‘H’ key to bring up the HUD, in order to actually make the changes that you wish to make.

My next post will probably use a number of other photos that I took at Dion and Caroline’s wedding, and will be for ‘The Face of Innocence’. As you can probably imagine, these photos will not be of the dance floor at the end of the night, but will be a selection of shots that I took of my friends’ children, which I am also quite pleased with.